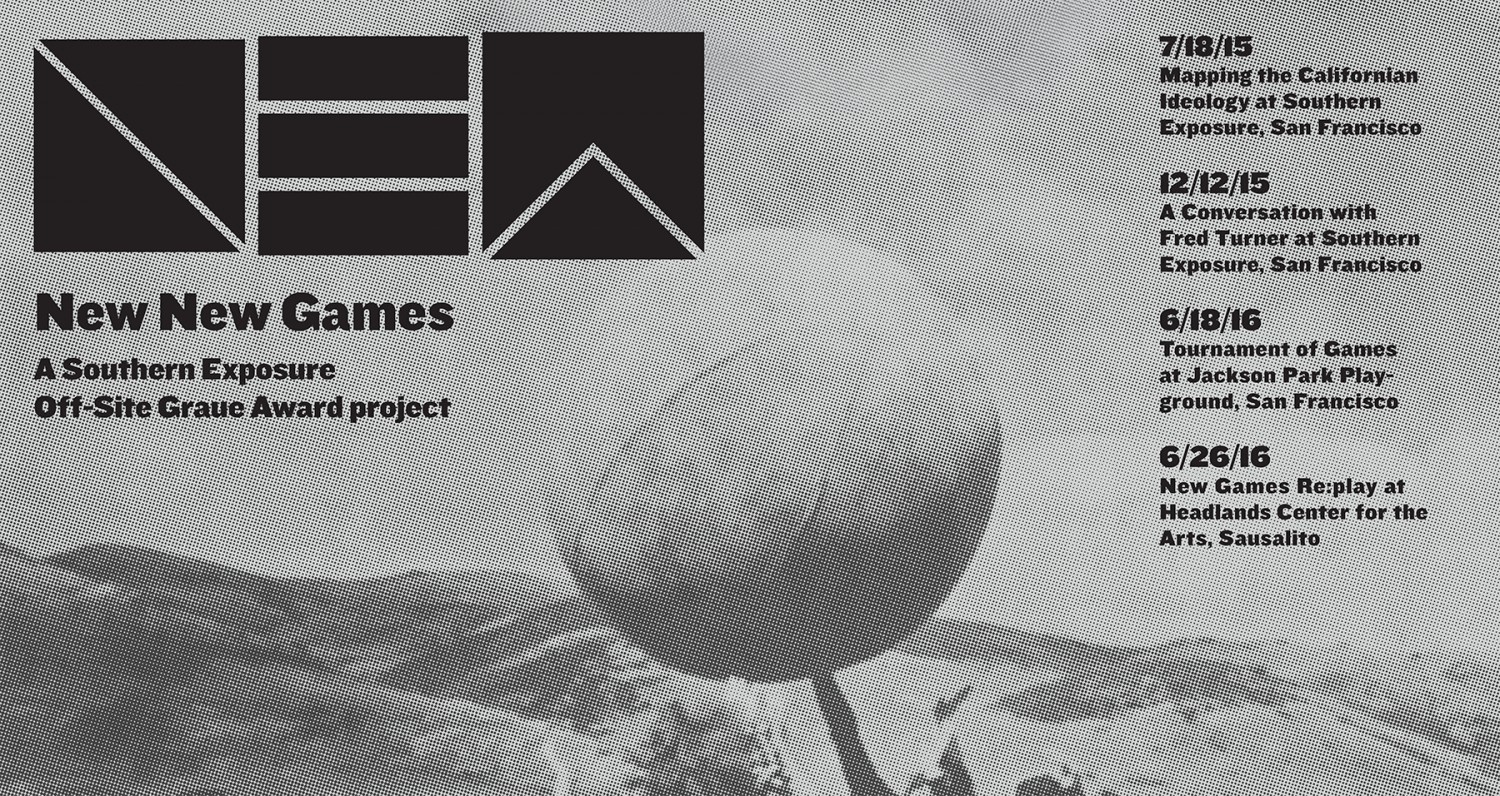

The Use of Play

Robby Herbst

Through the restructuring of play, New Games is attempting to bring man into harmony with his environment, provide space for families to play together, and eliminate the barriers of age, sex, race and economics, from leisure time activities. Rather than the winning-at-all-costs attitude, New Games brings joy and self-expression to the play process.

– Pat Farrington, first director of the New Games Foundation, 1975

From the distance of 40 years, what are we to make of New Games? New Games came with a generosity of time for human-to-human contact, space to gather, and a belief that play could have a part in changing the world. The New Games books were published in the hundreds of thousands. Its trainers trained tens of thousands of people in alternative forms of recreation, spreading the idea of creative, physical, low-cost pleasure to the world – a very serious concept for fun.

Happenings emerged in 1950s New York by way of artists John Cage and Alan Kaprow. This art form emigrated west with artists like Stewart Brand (then associated with the proto-psychedelic art collective USCO), and transmogrified into psychedelic community spectacles of pleasure[1]. Coupled with a Digger-infused notion of “free,” the politics of Woodstock are understood as the pleasure of unhinged association in a post-scarcity society.[2] In the Bay Area, New Games and its large public tournaments can be seen in parallel with other large-scale public movement events of its time. In Citydance, for example, dancer and choreographer Anna Halprin created and publicized an open movement score for a dance that began at sunrise on San Francisco’s Twin Peaks and ended at Embarcadero Plaza. The score (the rules of the dance) evolved as it drifted through the city’s neighborhoods and transit systems. In 1975, the New Games Foundation held a tournament in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. It hoped to bring the whole diverse city together to play games that would erase social boundaries and be fun. Ten thousand people showed up.

New Games, its feet damp in the Bay Area avant-gardes of Stewart Brand’s communitarian set and the human potential posse of George Leonard’s Esalen Institute, had much to offer in terms of the significance of public recreation in the life of a city; as an active form of individual gestalt therapy, a notion that it keyed into the value of social creativity, generativity, and social cohesion. Today, New Games continues to foster joyful experiences for many people through youth groups, schools, college rec programs, theater classes, corporate retreats and development seminars, but few are aware of the downright utopian ideas that informed its genesis.

In the first New Games book, Stewart Brand (who was instrumental in supporting the first New Games Tournament and the New Games Foundation) contributed an essay called “Theory Of Game Change.” It is a key to understanding the broad changes to the perceived value of play in our society over the past 40 years. Brand’s writing strings together thoughts about a very early computer game called Space Wars; how his own history has informed New Games, including a zap at a War Resisters League meeting in 1966[3]; an extended quote from Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga’s pivotal book on the role of play in society; and the following statement regarding the evolution of games and society:

You can’t change a game by winning it, goes the formula. Or losing it or refereeing it or spectating it. You change a game by leaving it, going somewhere else, and starting a new game. If it works, it will in time alter or replace the old game.

The logic of this statement fits well in Brand’s two terrains of operation: the back-to-the-land movement and Silicon Valley techno-utopianism. In our era of networked culture, his statement can be read as a declaration of the value of “disruptive” technology.

“We are coming together to celebrate our culture, social, economic, and racial differences,” states a poster for the 1975 New Games Tournament in Golden Gate Park. Seen through the lens of pleasure, this come-on speaks to the values of sharing and free-association at the center of New Games. But looked at through a secondary lens, you might ask the obvious question, “why would someone want to celebrate their poverty in a wealthy society?” Who wins when the ease of temporary distraction supersedes the unpleasant work of confronting structural inequality? Posed only in the light of a 1970s-era pleasurefest the question is overwrought, but in the context of the Bay Area’s current techno-libertarian atmosphere the question is profound. Who gets to change the game?

The dubiously named “sharing economy” strips workers of their economic stability and agency. After offering tax breaks to technology companies, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee declares a fiscal deficit and demands budget cuts in public agencies. Airbnb destabilizes housing in the region. Everyone knows someone who’s been evicted. Innovation in public education is sought at the expense of public education and the profit of private innovators. Public space and public lives are metered on private devices. Civic spaces are recoded for the benefit of the wealthy, marginalizing those without access to game-changing tools. Creativity is put to the limited service of economic worth.

Play is rehearsal for all kinds of group behavior. We begin to learn its codes from birth: play hard, play fair, nobody hurt.[4] Group games model ways groups can be together in a society, thoughtfully or otherwise. With New New Games, I am exploring ways that we are together. Today, the up-with-people collective attitude that spawned New Games in the Bay Area is replaced by the techno-libertarianism which looks at profit as a means to generate social good. The connection between the 1970s human potential movement and the neo-liberal ideology of today is territory trodden by critical thinkers.[5] There is a bridge between the innovation economy, the rule-breaking attitude of creatively oriented competition, and the economy of self-improvement of the ‘70s. Today the Bay Area feels this most pronouncedly through the extreme income disparities taking hold. And while New Games appears mostly as something fun, one can’t help but wonder if New Games had a part in preparing everyone to embrace the ideology of personal play and freedom over that of community wellbeing.

[1] Anyone interested in learning about the context that formed New Games should consider reading Fred Turner’s critical autobiography of Stewart Brand called From Counterculture To Cyberculture (University Of Chicago Press; 2008).

[2] The San Francisco Diggers were a group of Anarcho-Communalists operating in San Francisco in the mid-to-late 1960s. They helped to coordinate a network of communal spaces, organizations, and associations that liberated capital from time, organizing free stores, free concerts, free auto mechanics, free housing and more. They refused the politics of scarcity, liberating “free” from the fat of a wealthy society.. Later in the decade, their politics and ecstatic ideas were advanced by the Yippies. Yippie “leader” Abbie Hoffman theorized that the Woodstock concert was a founding event for a culture of liberated youth existing on the currency of love, sex, drugs, and revolutionary rock-n-roll in a post-capitalist world.

[3] Brand refereed a game of slaughter. He suggests that his intent was to implicate the members of this peace group in the culture of violence that they rejected by enjoining them in a rough and hyper- competitive game.

[4] This is the New Games motto.

[5] For an example, view Adam Curtis’ essay film The Century of The Self.