New New Networks

Valerie Imus

A viral video circulating in the fall of 2014 depicted a confrontation that took place in a San Francisco Mission district public park between a group of young men and teens who typically play pick-up soccer there, and a group of adults in tech company t-shirts who had reserved the field online for a $27 fee. The deeply charged interaction and subsequent outrage in response to the video points to the tense relationships between current Bay Area residents with differing perspectives of the cityscape. It also highlights our ongoing shift from freely accessible public space to increasingly privately controlled urban areas. As the population of San Francisco transforms from a culturally and economically diverse population, to one with a large number of very well-paid workers relocating to the area for highly competitive jobs in the tech industry, so have we shifted from improvisatory relationships with our shared urban space to restrictions granting availability to the highest bidder. Streets that were previously available for free-form community activities (albeit at times subjectively organized and specifically gendered) are increasingly organized by regulation with an eye toward the sole benefit of for-profit interests.

These parallel trajectories, while not unique to the Bay Area,. are symptoms of a large-scale economic shift towards global neoliberalism. The Bay Area continues to be haunted by the powerful specter of a hopeful counter-culture held up as foil to our contemporary cynicism and alienation, but one can draw a neat line between a neoliberal doctrine that privileges personal liberty in the marketplace and the ideals of a Bay Area counterculture emphasizing personal expression above all else (setting aside for the moment counter-cultures rooted in specific political agendas). Both primarily value the new and the cool, and both embody a rhetoric that aims to step outside of political engagement. Pursue these ideals down a path long enough, and you’ll arrive in present-day San Francisco.

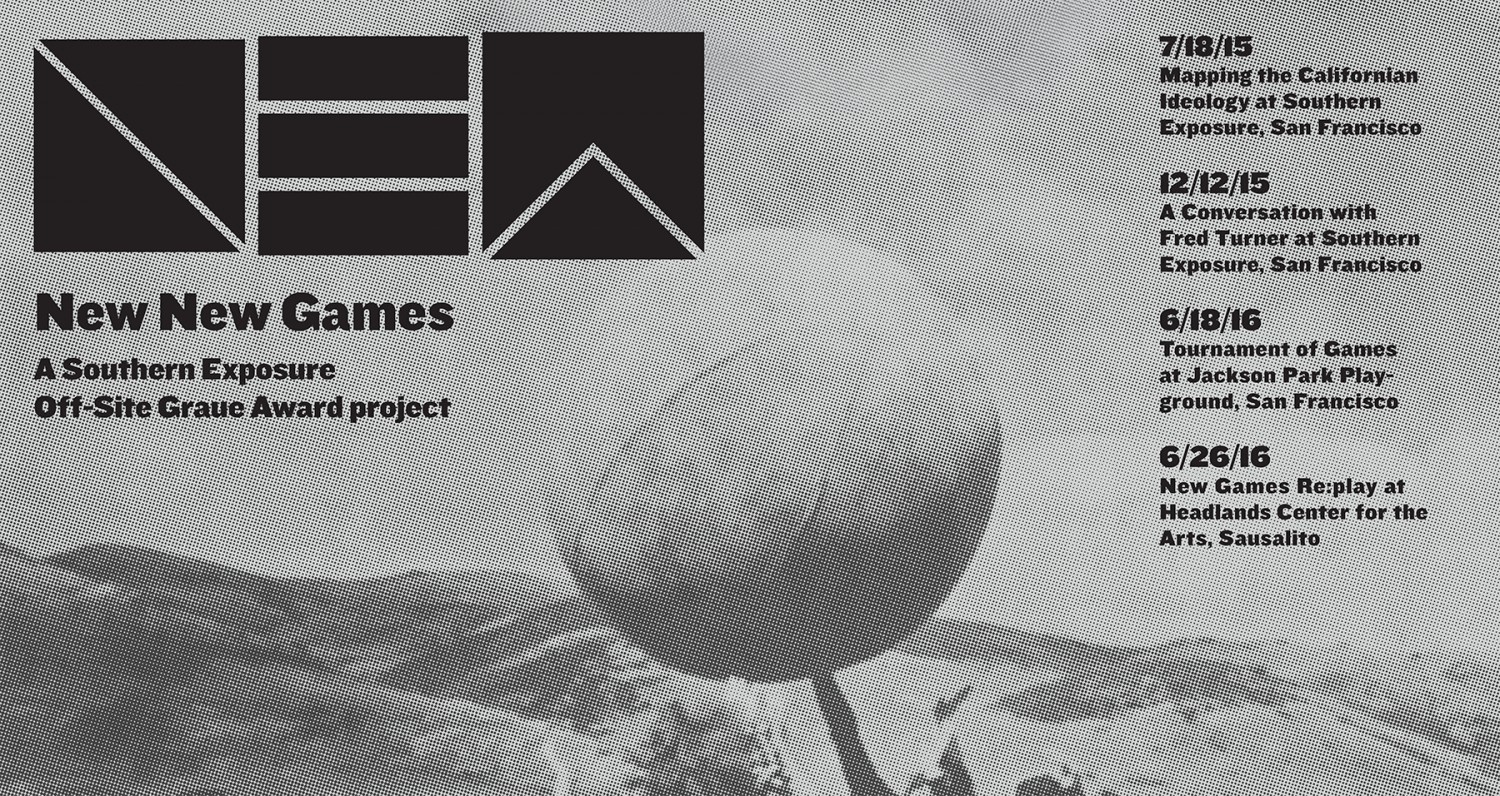

Robby Herbst’s New New Games, a Southern Exposure Off-Site Graue Award project, is an invitation to collectively consider these cultural shifts in public landscape. The project consists of a series of conversations about the evolution of techno-libertarianism on the West Coast; a participatory event re-imagining public games happenings of the 1970s as a means of collectively thinking about public space; and this publication. All take inspiration from the 1973 New Games Festival, instigated by Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, with other collaborators.

Stewart Brand was producing events with the Merry Pranksters in San Francisco when he was invited in 1966 to develop a group activity for the War Resisters League at San Francisco State College. In a provocative effort to encourage players to act out aggressions in a non-competitive public space, he designed a series of group games using a large ball painted to look like the earth (The Earthball). This sparked a series of participatory events, and in 1973, Brand used proceeds from the last Whole Earth Catalog to fund the New Games Tournament in Gerbode Valley in the Marin Headlands. The festival was co-organized by Pat Farrington, a Bay Area community organizer, and brought together referees to lead about 6,000 participants in numerous games over two weekends.[1] The event launched the New Games Foundation, which continued to train individuals in New Games until the organization folded in 1985.

The Whole Earth Catalog had envisioned a disembodied and networked community sharing ideas – a vision which later fueled Brand’s involvement in building other virtual spaces like such as the Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link (WELL), an early online community.[2] A similar utopic vision of self-organizing networks outside of managing systems continues to drive much of the philosophy around the current Bay Area tech community. However, networks based on an unregulated market-driven economic system are solipsistic by nature and can encourage social conditions that are exclusive, heteronormative, classist, and racist. The imagining of a unified world (as pictured on the Earthball and cover of the Whole Earth Catalog) sounds wonderful but can easily gloss over and problematize difference.

The landscape of San Francisco has changed dramatically with the rising cost of real estate and the shuttering of many small businesses. As rental costs and evictions in the Bay Area continue to rise, many people of color, the working class, and artists have been forced to leave the region.[3] Many commercial art galleries and mid-size non-profit spaces have closed or relocated. With a large, growing population of contractual, contingent laborers with a whose working relationships are primarily virtual, the Bay Area is losing not only its public space but its face-to-face connections. We may be networked, but whether we’re a community is certainly debatable.

The originators of New Games turned to the notion of play as an enactment of possibility and connection, one which has the potential to open up a rupture between our actions and the production of capital. They looked to games as a way of creating and negotiating new strategic models of our relationships. According to The New Games Book, games were another tool, like those meant to be accessed in the Whole Earth Catalog as a “means by which people could realize their own visions of living, shape their environment accordingly.” However, into the imagined, utopian space of games, we carry with us existing roles and relationships.In New New Games, Robby Herbst invites us to look at the flawed utopian ideas of the present moment through the lens of the past, and asks us to consider what it means to re-enact the impoverishment of utopianism. Re-enactment as a strategy in contemporary art often functions to highlight commonalities and disjunctures between the present and the mythologies of our pasts. Is it possible to imagine new strategies by destabilizing these narratives? By enacting the rituals of New Games together within the current fraught landscape of San Francisco, it’s unlikely that we will dramatically shift the rules of the game, but perhaps we can find a playful, more expansive perspective on things. Ultimately, the question remains, can we share the field?

[1] Pat Farrington was the first director of the New Games Foundation when it was incorporated in 1974.

[2] We are indebted to Fred Turner, and in particular his book From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

[3] According to the US Census Bureau, in 2000, 7.8% of San Franciscans identified as African American or Black, while in 2010, 6.2% did so, and in 2014 the population was estimated to be 5.7%. In September 2015, the San Francisco Arts Commission released the results from its Individual Artists’ Space Need Analysis, finding that of nearly 600 artists, 70% had been or were being displaced from their studio space, home, or both. (http://ww2.kqed.org/arts/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/09/Individual-Artists-Space-Need-Analysis_FINAL.pdf)